it's almost all about housing

- Written by Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute

Compared to the rest of the world, income inequality is not particularly high in Australia, nor is it getting much worse.

The real problem is housing inequality.

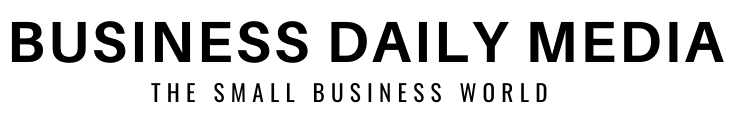

Rising house prices have increased wealth inequality[1]. Rising housing costs have dramatically widened the gap between high and low disposable incomes.

The gap between low-income and high-income households in Australia is close to the OECD average[2]. Income inequality – measured by the gini coefficient – has fallen[3] slightly over the past decade.

The Productivity Commission[4] says inequality has increased only slightly in the past three decades. Economists at the Reserve Bank[5] have come to similar conclusions.

But inequality is growing once housing costs are factored in, with the poor being hurt the most.

Incomes for the lowest 20% of households increased[6] by about 27% between 2003-04 and 2015-16. But their incomes after housing costs increased by only about 16%. Low-income Australians are spending much more[7] than they used to keep a roof over their heads.

In contrast, incomes for the highest 20% of households increased by 36%, and their after-housing incomes by 33%.

Leaving the young and poor behind

Home ownership is increasingly benefiting the already well-off. Since 2003-04, increasing property values have contributed to the wealth of high-income households increasing by more than 50%. Wealth for low-income households has grown by less than 10%

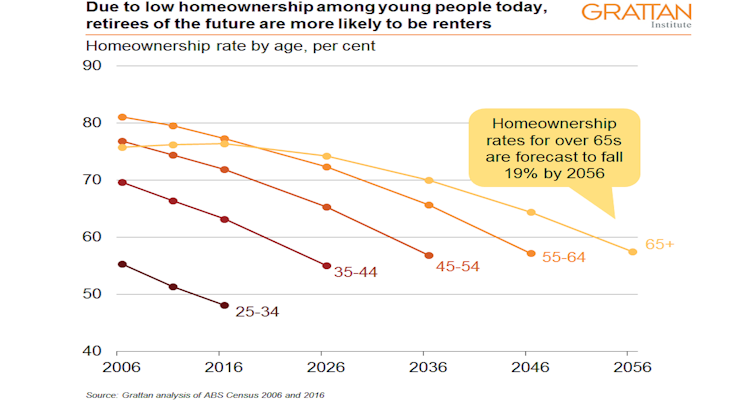

As we’ve noted previously[8] rising housing costs have widened the gap between renters and home owners. As property prices have escalated, the higher deposit hurdle has seen rates of home ownership falling fast among the young and the poor.

In 1981 more than 60% of those aged 25-34 had a mortgage; by 2016 it was 45%. The trends are similar among older groups. In the same period, home ownership among the poorest 20% of households has fallen from 63% to 23%.

The big winners of the property boom have typically been older typically Australians lucky enough[9] to buy a house before prices took off. Housing has thus compounded inequality between the young and old[10].

This could lead to higher inequality in the future, because the children with wealthier parents can rely on the “bank of mum and dad” to break into the housing market, and then inherit their parents’ home as an investment property.

Many low-income Australians won’t be so lucky[11], which is why the share of Australians who own their homes is expected to fall sharply[12] in the decades ahead.

As we’ve noted previously[8] rising housing costs have widened the gap between renters and home owners. As property prices have escalated, the higher deposit hurdle has seen rates of home ownership falling fast among the young and the poor.

In 1981 more than 60% of those aged 25-34 had a mortgage; by 2016 it was 45%. The trends are similar among older groups. In the same period, home ownership among the poorest 20% of households has fallen from 63% to 23%.

The big winners of the property boom have typically been older typically Australians lucky enough[9] to buy a house before prices took off. Housing has thus compounded inequality between the young and old[10].

This could lead to higher inequality in the future, because the children with wealthier parents can rely on the “bank of mum and dad” to break into the housing market, and then inherit their parents’ home as an investment property.

Many low-income Australians won’t be so lucky[11], which is why the share of Australians who own their homes is expected to fall sharply[12] in the decades ahead.

A clearer policy agenda

Despite the clear evidence housing is key to inequality in Australia, housing policy is thin on the ground.

In the dying days of the federal election campaign, the Coalition announced a plan[13] to help those struggling to save the 20% deposit normally required to buy a home.

The federal government has also made it easier for people to access their super[14] to pay the deposit.

These policies might be popular but do little to improve housing affordability for low-income earners; they might even do more harm than good[15].

Labor, meanwhile, ran with a proposal[16] during the last election campaign to build 250,000 new affordable housing dwellings, using a mechanism similar to the earlier National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS). On our analysis[17], though, the original NRAS was poor value for money, and did not target those most in need.

Read more:

Rudd's rental affordability scheme was a $1 billion gift to developers. Abbott was right to axe it[18]

Addressing inequality requires a clearer view on what to do about rising housing costs.

The priority should be to boost Rent Assistance[19] by 40% – an extra A$1,410 a year for singles and A$1,330 for couples – and benchmark it to rents paid by low-income renters.

The federal government should also give more funding[20] to the states for social housing carefully targeted to people at serious risk of homelessness.

Emulating the Rudd-era Social Housing Initiative[21], which resulted in 20,000 new social housing units being built and thousands more refurbished at a cost of A$5.6 billion, would provide a much-needed boost to housing construction when the pipeline is drying up[22].

Supply-side economics

But redistribution alone won’t be enough. Housing is a A$6.6 trillion market. Subsidies can only paper over market failures arising from overly strict zoning rules that prevent greater density[23] in our major cities.

Housing inequality will really only fall if housing costs fall. That requires building more houses. We estimate[24] building an extra 50,000 homes a year for the next decade would make house prices and rents 10% to 20% lower than they would be otherwise.

This is primarily a challenge for state governments. They govern the local councils that set most planning rules and assess most development applications. But the federal government can and should encourage[25] the states to boost housing supply by reforming land-use planning and zoning laws.

If Scott Morrison really believes in “a fair go for Australians[26]”, he needs to tackle the housing crisis.

A clearer policy agenda

Despite the clear evidence housing is key to inequality in Australia, housing policy is thin on the ground.

In the dying days of the federal election campaign, the Coalition announced a plan[13] to help those struggling to save the 20% deposit normally required to buy a home.

The federal government has also made it easier for people to access their super[14] to pay the deposit.

These policies might be popular but do little to improve housing affordability for low-income earners; they might even do more harm than good[15].

Labor, meanwhile, ran with a proposal[16] during the last election campaign to build 250,000 new affordable housing dwellings, using a mechanism similar to the earlier National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS). On our analysis[17], though, the original NRAS was poor value for money, and did not target those most in need.

Read more:

Rudd's rental affordability scheme was a $1 billion gift to developers. Abbott was right to axe it[18]

Addressing inequality requires a clearer view on what to do about rising housing costs.

The priority should be to boost Rent Assistance[19] by 40% – an extra A$1,410 a year for singles and A$1,330 for couples – and benchmark it to rents paid by low-income renters.

The federal government should also give more funding[20] to the states for social housing carefully targeted to people at serious risk of homelessness.

Emulating the Rudd-era Social Housing Initiative[21], which resulted in 20,000 new social housing units being built and thousands more refurbished at a cost of A$5.6 billion, would provide a much-needed boost to housing construction when the pipeline is drying up[22].

Supply-side economics

But redistribution alone won’t be enough. Housing is a A$6.6 trillion market. Subsidies can only paper over market failures arising from overly strict zoning rules that prevent greater density[23] in our major cities.

Housing inequality will really only fall if housing costs fall. That requires building more houses. We estimate[24] building an extra 50,000 homes a year for the next decade would make house prices and rents 10% to 20% lower than they would be otherwise.

This is primarily a challenge for state governments. They govern the local councils that set most planning rules and assess most development applications. But the federal government can and should encourage[25] the states to boost housing supply by reforming land-use planning and zoning laws.

If Scott Morrison really believes in “a fair go for Australians[26]”, he needs to tackle the housing crisis.

References

- ^ wealth inequality (theconversation.com)

- ^ close to the OECD average (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ has fallen (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Productivity Commission (www.pc.gov.au)

- ^ Reserve Bank (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ increased (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ much more (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ noted previously (theconversation.com)

- ^ lucky enough (theconversation.com)

- ^ inequality between the young and old (theconversation.com)

- ^ won’t be so lucky (theconversation.com)

- ^ fall sharply (theconversation.com)

- ^ plan (theconversation.com)

- ^ super (www.ato.gov.au)

- ^ do more harm than good (insidestory.org.au)

- ^ proposal (theconversation.com)

- ^ analysis (blog.grattan.edu.au)

- ^ Rudd's rental affordability scheme was a $1 billion gift to developers. Abbott was right to axe it (theconversation.com)

- ^ boost Rent Assistance (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ more funding (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ Social Housing Initiative (www.nwhn.net.au)

- ^ drying up (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ prevent greater density (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ estimate (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ encourage (grattan.edu.au)

- ^ a fair go for Australians (www.theaustralian.com.au)

Authors: Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute